I finally watched the Barbie movie.

I always have a hard time watching something when it’s relevant. Last year, Barbie was at the center of public discourse. Conservative commentators freaked out about the film; liberals lauded it. The consensus opinion that developed was that this was an important film. It may seem like a fun, big budget adaptation of a major intellectual property, like The Super Mario Bros. Movie (2023) the same year, but this one actually had something on it’s mind. It’s reflecting on the cultural meaning of Barbie. It’s a feminist film. Hell, they even got Greta Gerwig to direct the thing.

Barbie has returned to the discourse in light of the Oscars. Again, taking it’s role as important film, the Academy snubbing the film for an Oscar nomination has lead to an outcry, Barbie even receiving some support from Hillary Clinton.

I’m not really interested in battling about whether or not Barbie (2023) is a good film or worthy of an Oscar. It was a fun film with some incredibly cool set design and some witty writing that got laughs out of me. Greta Gerwig is a talented director, and the film certainly shows that off. The film is pretty unapologetic about it’s liberal perspective, which naturally brought some ire from conservatives. I don’t think that’s a mark against the film. With the type of film it’s trying to be, pissing off someone like Ben Shapiro makes it more attractive, not less.

The culture war flare-ups surrounding the film aren’t accidental; they’re part of the design. The film certainly positions itself within the broader discourse. Gerwig was doing her best to make a provocation within the confines provided by a major IP receiving corporate oversight, and she did a great job within those confines.

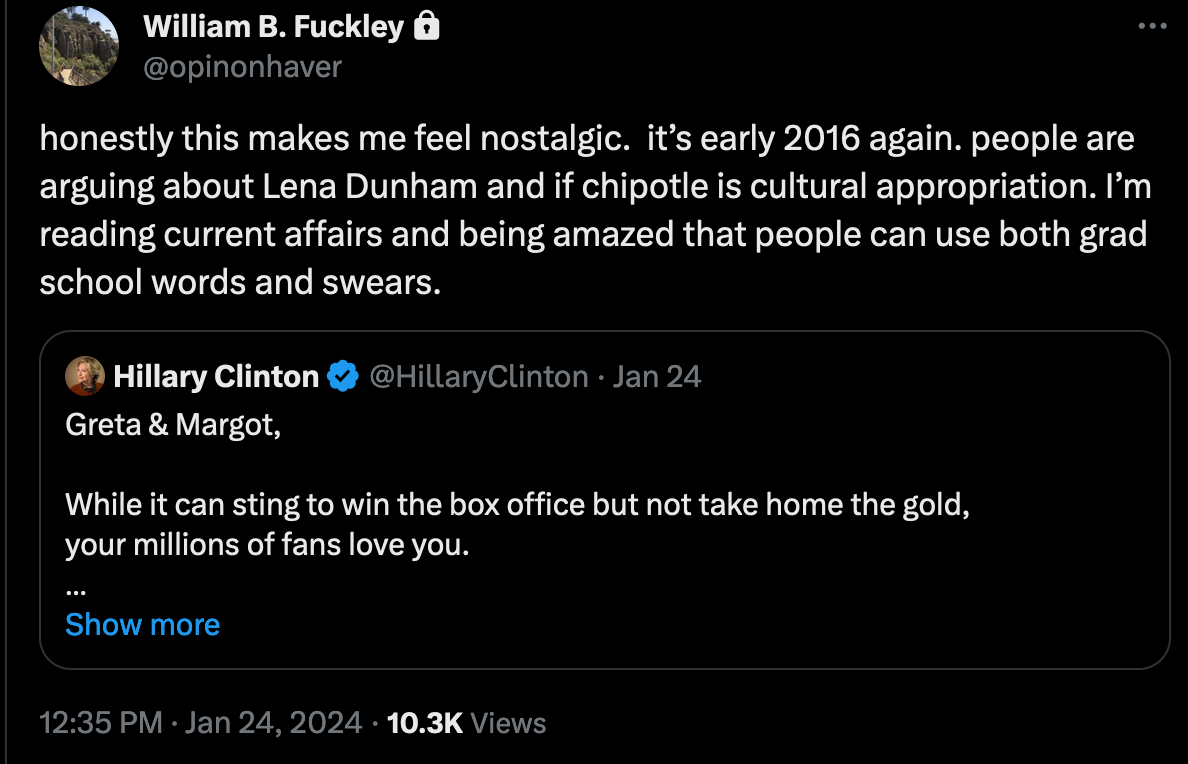

Nevertheless, something feels tired about all of this. The Twitter user @opinionhaver made a joke about Hillary Clinton’s contribution to the Oscar discourse that has sat in my head.

That’s what it is. This discourse all feels a decade old. The film’s perspective also felt this way. Despite being a major cultural artifact supposedly reflecting the state of women’s issues in America, the film felt more in line with the 2010s pop feminism that has fallen somewhat out of a favor in recent years. This is more of an observation than a value judgment—I don’t feel confident enough as a straight man to make a judgment on Gerwig or Barbie’s take on patriarchy. What I can say is that the film feels haunted with old discourses.

The aspect of the film I found genuinely unsettling was the diegetic appearance of the company, Mattel. This is where the strange, postmodern aspect of the film really came out. It takes Barbie—a character playing the Platonic form of the commodity, the toy—and puts her in conversation with criticisms of Mattel. These dolls gave girls unrealistic expectations for themselves. These toys represent the Platonic form of American femininity with all it’s contradictory and unachievable signifiers. Barbies shape young girls’ notion of womanhood, and yet their material purpose is as commodities; Mattel wants to be progressive, but as a company they are, by definition, driven by profit. How will Barbie vindicate herself in light of this?

The film tries to build itself around that tension. We are watching a brand become self-conscious and criticize itself. There’s something bold about this, right? An explicitly branded product is telling you the bad things about itself. A Mattel movie about a Mattel product frames Mattel’s board as exclusively male, despite this not even being the case. It pokes fun at its own censoriousness when one character says “motherfucker,” but is bleeped with a Mattel logo appearing over her lips—even more of a self-referential joke, since a test screening didn’t censor the word, likely implying Mattel did ask for it to be censored.

The weirdest thing about this branded self-criticism is how little of a deal it is. The strangest part is that this didn’t feel very strange. I accepted the concept of an advertisement insulting it’s own company really easily. It’s such a normal component that the appearance of Mattel’s board in the film has hardly been mentioned in the discourse around the film. It almost feels like a trite point to make. It’s a cliché. The film feels haunted by old conversations.

Doing a Domino’s

In 2009, a video of two Domino’s employees went viral on YouTube. In the video, one employee sticks cheese up his nose before putting it on a sandwich to the amusement of the other employee filming it. The little prank became a public relations crisis for Domino’s, and lead to felony charges for both of the employees involved.

It may be hard to remember the early years of social media becoming ubiquitous. This story was notable in 2009 partially because it was an early example of online outcry against a company. This was a new phenomenon that companies weren’t quite sure how to handle. The outcry to the video forced Domino’s to make a Twitter account.

Domino’s was in a bad spot in 2009. It wasn’t just the viral video. The general perception of Domino’s at the time was that they were fast but incredibly shitty. The video reinforced a broader consensus about the company. The food was gross. Sure, they may have invented pizza delivery in the 1960s, but that wasn’t much of a novelty in 2009, and they had sacrificed quality in the process of maintaining speedy delivery.

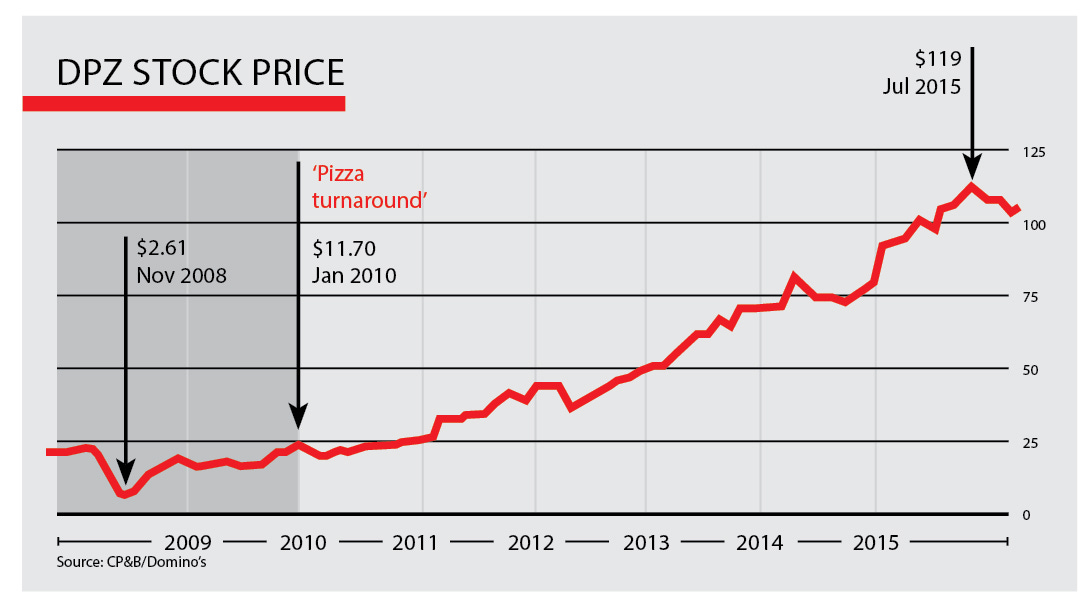

At the very end of 2009, right around the holidays, Domino’s launched an ad campaign engineered by Crispin Porter & Bogusky that was their salvation. It was a bit of a shocking marketing tactic at the time; I recall family members commenting on it at the time wondering if it would work. With a decade of hindsight, it’s now clear that it was one of the most successful ad campaigns of the past few decades. Here was the basic idea: admit to everything.

The campaign, called the “The Pizza Turnaround,” was produced like a documentary. It showed numerous talking heads, workers and executives at Domino’s, responding to the negative feedback the company had received. “We get this one a lot,” a woman says about a comment saying the crust “tastes like cardboard.” We then see the CEO, Patrick Doyle, tell us that they are taking this feedback seriously.

Unlike those insincere other companies, Domino’s takes its customer feedback seriously. They’ve been in the labs cooking up a new and improved product. They are owning their past mistakes, and they are seeing them as exciting opportunities to grow.

While claiming that your products are new and improved is as old as advertising, the admission of guilt took people off guard. This was intentional. The company laid out the strategy in a case study brief after winning the 2011 David Ogilvy Award.

Populist anger seemed to keep building even after companies went bankrupt, CEOs went to prison and fines were levied. Why did people seem unable to forgive these companies, we wondered?

One thing we saw again and again in qualitative research: companies never admitted they were wrong. They fought and delayed and fired people. They revved up the PR engines. But they never simply said, “Hey – we screwed up.”

Admission is interesting. It’s humanizing. When a company admits they’re wrong they begin to seem human, fallible and vulnerable. Admission changes the perception of intent. What might have seemed like a deliberate act of greed or dishonesty instead looks like a mistake or bad judgment. But most of all, admission lays the foundation for a new relationship. It’s like a reset button. Without admission of wrong, there can be no real reconciliation.

They go on.

We took scripts into creative development focus groups. There, we discovered that the disruptive nature of admitting our failure was so compelling that it likely outweighed the potential risk of disparaging our own product.

This is the key aspect of the Pizza Turnaround campaign. While disparaging your own product may seem, at face value, to be a stupid marketing decision, it can also be an incredibly useful strategy. At the time, this was such an unexpected move that it made people receptive. At the very least, it made enough of an impact that I still remember it, despite never really caring for even the “new and improved” Domino’s. In the years following, “Doing a Domino’s” became shorthand for a company disparaging it’s own product or doing a large act of contrition in order to rebrand themselves.

Hyperpolitics

In Anton Jäger’s 2023 article, “Everything is Hyperpolitical,” he lays out the transition from 20th century mass politics to the “post-politics” of the late 1980s and early 90s—a phenomenon that now seems to be giving way to something new which he is calling “hyperpolitics.” I promise this will connect to Barbie and Domino’s.

The era of mass politics was an era of parties. It was an era of ideological conflict and militant interest groups. Politics was something that happened when you, as an individual, sacrificed some agency in the process of becoming a collective, a class, or a party.

This is a distinctly Cold War moment. There were a lot of different ideologies on the menu—liberal, capitalist democracy was one, but so was communism, fascism, social democracy, etc. These ideologies were represented by a party. To be a “communist” didn’t just mean holding a certain set of beliefs, although that was part of it—it was also membership in a collective.

With the 1980s came neoliberalism, the erosion of the public sphere into the private, the selling off of public assets to contractors and technocrats, and the relegation of history and conflict to the backburner. As the Soviet Union fell, so did an existing alternative to liberal capitalism, and thus began Francis Fukuyama’s famous “End of History.” There is no longer a political project possible after the ascendancy of liberal capitalism; no alternatives remained. Mark Fisher would also famously refer to this phenomenon as “capitalist realism.”

With this came a turn away from institutions and collectives. This begins an era of hyperindividualism and self-help. Any existing pain or suffering was relegated either to individual psychology or to charitable, non-profit endeavors that fit within the existing political system. The drive for liberation became one for personal liberation and hedonism (nothing collective, though). Revolution was replaced by self-actualization. This was the post-politics era, which began in the 1980s and continued on for several decades.

Jäger believes that this moment is ending. Sort of. Ever since the 2008 financial crisis, the end of history has “begun, steadily, to thaw.” Early forms of it were apparent in the Occupy Wall Street movement, although this mass movement struggled to find the language or tactics necessary to force its will on the economic order. Since 2016 and the election of Donald Trump, politics has returned even more steadily, and since 2020—the pandemic and the protests—the process has continued further.

Unfortunately, institutions and collectives are still eroded. While mass protests do take on the character of a collective, they don’t seem able to actually force their will on the establishment in the way mass politics once did. 2020 was the biggest protest movement the U.S. has ever seen, and while it accomplished a lot in the battle of changing general sentiment toward racial issues, almost none of the hard-won reforms actually happened. Politics did not result in policy, in part because of a split that took place during the post-politics era. Jäger writes,

All the critiques of post-politics recognized the separation between “politics” and “policy.” On the one hand, politics named the formation of a collective will that determines what society would do with its surplus materials. Policy, in turn, relied on the execution of that will. In the 1980s and 1990s, when the politics of crisis steadily turned into a crisis of politics, these two moments underwent a mutual estrangement. The determination of the collective will was relegated to a mediasphere addicted to novelty and run by public-relations experts, while the execution of policy was handed over to unelected technocrats. In the widening of this separation lay the seeds of a transition from post-politics to hyperpolitics.

As politics returns without any structures or collectives, all it has is cultural moments. Even at it’s most intense, like the protests of 2020, this politics is only capable of public expression and rarely actual change. Jäger goes on,

Rather than concrete results or new social relations, this political tendency seems to mark its influence by its ability to reproduce its frenetic form of activity, something it has had special success doing at nonprofits, in the media and in an increasingly digital public sphere—not to mention in the minds of those who consume these cultural products. Hyperpolitics comes and goes, like a neutron bomb that shakes the people in the frame but leaves all the infrastructure intact—an awkward synonym rather than an antonym to post-politics.

In this, politics is guided by the same logic any other cultural product is. Without any existing political apparatus or party or organization, politics is relegated to the same realm as all other collective sentiment: public relations, marketing, and behavioral economics. There becomes no meaningful difference, aside from the emotional and moral commitments of those participating, between a large, serious protest about an important problem and Rick & Morty fans rioting at a McDonald’s, Kai Cenat fans swarming Union Square Park, or a huge group participating in Barbenheimer. It’s all the same noise and headlines, flattened by the reaction and discourse on social media.

All we have is public outcry—something that is ultimately defeated by good PR.

Defeating public outcry

It wasn’t apparent that the “thaw” and the rise of social media was going to lead to hyperpolitics. In the years surrounding Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring, it seemed like public outcry was now a unique and direct form of democratic engagement made possible by social media. Authoritarian regimes couldn’t control the free speech permitted by the internet. Corporations were now more and more at the hands of online outcry.

In the early 2010s, you could say that the internet was going to save the world and not get laughed out of the room. While companies like Domino’s scrambled to deal with negative press and perform contrition in advertisements, you could be forgiven for thinking that this was the dawn of a new era where the people ran things. It would take the failures of the Obama administration, disasterous outcomes in the Middle East, and the impotence of Occupy in the face of Wall Street to really show that the structure wasn’t going to bend to this new digital democracy.

As political sentiment continued to heat up, the optimism about social media faded. In part, this was because of the realization that unsavory people were also able to utilize the internet’s democracy, but it was also because corporations and technocrats figured out how to use the internet.

That 2010s democratic tech-optimism came out of a moment when companies were being taken off-guard by the internet; the mistake was to assume that this corporate subservience to public outcry was the new state of things rather than a momentary lapse. The Pizza Turnaround was an early and successful attempt by a corporation to not only save face, but to actually profit off of online outcry.

By choosing to come off as sincere and honest, accountable and willing to change after receiving feedback, the company was able to calm any outcry and even erode at the negative sentiment they’d built up over the years. This is part of a revolution in marketing and company engagement with online spaces.

From there, we saw Twitter accounts for companies pretending to be relatable or have depression. We’ve seen more and more companies willing to take careful and strategic political stances on things like racism or LGBTQ issues. The lesson from the Pizza Turnaround for many companies was that companies need to seem like a person, relatable, sincere, and, yes, fallible. Who doesn’t occasionally spill some oil in the ocean, after all?

We’re far enough away from 2009 that none of this feels particularly novel anymore. We’re all aware that brands are trying to be people, and most people don’t find a brand tweeting about how hard “adulting” is to be fun and relatable anymore. And since politics is culture and culture is consumption in this new, hyperpolitical age, the battlelines for politics are increasingly about marketing campaigns, films, and products. Last year, we watched months and months of right wing handwringing about Bud Light paying trans influencer, Dylan Mulvaney, to advertise their product. Right now, we’re watching endless and baffling right wing hysteria aimed at Taylor Swift.

Companies are learning to work within the hyperpolitical age, in the same way that they learned to adjust to the first examples of online public outcry. They are trying to figure out how to relate to the culture war. Do they intentionally take a side? Do they try to frame themselves as above it?

Mattel has, for the most part, seemed to approach the question by embracing the liberal positions on social issues. In 2016, Mattel released presidential dolls to “inspire girls to believe they can be anything—including leader of the free world.” The same year they released Barbies with new body types, and then in 2019, Mattel launched the “world’s first line of gender-neutral dolls.” In 2020, Barbie launched a doll commemorating Jean-Michel Basquiat, an homage that “highlights his prolific body of work that elevated street art and gained well-deserved acclaim in the upper echelons of the art world.” In 2022, they introduced “Dr. Jane Goodall and Eco-Leadership Team Certified CarbonNeutral® Dolls made from recycled ocean-bound plastic.” In 2023, they debuted a Barbie with Down syndrome.

None of these are bad things. I think the choice to represent different body types or disabilities, to commemorate Basquiat, or to say that women can and should be in political power are all good things to do. But it should be obvious that this is also a marketing tactic. They are learning to work with the culture war, and they are succeeding. By choosing a side in the culture war, you can even take advantage of public outcry—if unsavory pundits like Steven Crowder are mocking the Down syndrome Barbie, that makes Mattel look pretty good.

They are wanting to come off as sincere and in-touch with the political issues of our time. This is not because they want any genuine, radical change but because politics is culture now, and culture is patterns of consumption. Barbie (2023) was incredibly popular and has been able to hold on to the public conversation because of the talent and creativity behind it as an endeavor. But the appearance of the Mattel board in the film is a hyperpolitical object and an ominous reminder of the actual function of a film like this: to remind everyone that, yes, Mattel has made mistakes in the past, and, yes, Barbie dolls have contributed to sexist stereotypes about women, but, no, you shouldn’t worry—they hear your feedback and they are better now.

As I said at the beginning, I’m not very interested in discussing whether or not Barbie is a good movie. I had fun watching it. I’m not trying to moralize about Mattel or criticize their choice to appeal toward liberal audiences. At the end of the day, none of this is really out of the ordinary, and we all know the culture war is bullshit to some degree or another. The troubling thing for me is the knowledge that companies are getting smarter and smarter about hyperpolitics and learning to incorporate criticism or dissent into their own branding. Barbie is a political object and an intentional provocation, trapped within the only realm politics really happens anymore: the realm of marketing. It points to a disturbing picture of the future, companies doing a Domino’s—forever.